For 20 years I had a nightmare almost every night. Sometimes it

disappeared for two or three weeks and then returned with renewed force:

In the center of the city where I was born, I walk into an old

and very familiar house. Up to the age of six, when my father died, he

often took me there to visit his friend, an old man, a tailor called Katz,

and his daughter Veronika, who was also my age. I walk up the spiral

staircase and with my right hand I hold fast to the wrought-iron banister.

The stairwell has no windows and is badly lit. I climb up – higher and

higher. Just before I reach the sixth floor, the staircase breaks. I fall

into the depths, into the darkness, into an abyss. My heart is beating

frantically. I know that within seconds I will crash onto the stone floor

and be dead. Just before this happens I wake up and am exhausted with

fear.

This nightmare never returned from the moment that I was

able to say loud: "My father was a Jew." That was twenty years after his

death. The road to that sentence had been long and painful. My father

survived the Nazis in hiding. He never spoke to me about this period of

his life. And the feeling of having to be in hiding never left him.

Without knowing it, I imbibed all his fears, and they poisoned my life.

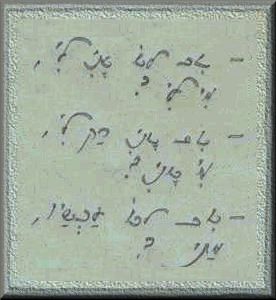

His indirect messages told me:

YOU ARE MY ONE AND ONLY – YOU ARE MY LIFE

BE VERY GOOD – BE ABOVE AVERAGE; BUT NEVER BE CONSPICUOUS: THAT

IS DANGEROUS.

And there was the unspoken message, never to talk about

"THAT", not even within the family. He never told me he was Jewish. It was

not to be talked about, but for me the subject was ever-present.

There was one place – an island – on which the unbearable wounds

could be laid bare about, although often enough they were only insinuated:

It was Mr. Katz’ flat where my father met with other survivors. I knew

them as Uncle Paul, Uncle Gerhard, Uncle Alfred, and others. Regularly

Veronika and I sat between them. Our fathers and the other men were

convinced that "the children don‘t understand". But I took it all in:

before I had ever heard the word I knew what deportations were. One of

Uncle Paul’s stories I never forgot: He had been in Auschwitz. Every

morning the prisoners had to line up to be counted. At various places the

snow was yellow with the frozen urine spilt at night by those who had not

managed to get to the latrine in time. The count decided on who was to

chew off the yellow bits of the snow and swallow it so that it became

white again. "Ordnung muss sein!". Order had to be maintained.

Veronika and I sat crouched under the table where we were

expected to play and held each others hands in silence. The world of our

fathers enveloped us and yet it was far away. I had a feeling of

everything being unreal. The whole world was alien and hostile. I froze up

inside. Death breathed from every corner. This room was home for the many

dead who had not returned. Here, these men set up the grave-stones of

memory and took them with them when they left. In my memory, Mr. Katz’s

flat was gloomy, oppressive and dark. Years later I accompanied a

girl-friend to a pleasant, light and large flat in which a doctor had set

up his practice. It was the self-same flat that had once belonged to Mr.

Katz.

It is from this period that I also remember warmth, security and

belonging, celebrating, and joking. They had been rescued! I also remember

various melodies and moods of a synagogue. It was so different to when my

father once showed me a church where a mass was taking place. Here I was

not allowed to put questions or run around. I was urged to keep still.

People looked at me disapprovingly. I did not know why. I was happy that

we did not stay long.

Every evening, my father told me "invented" stories. My mother

said that only his sudden and unexpected death prevented him from writing

a book of fairy tales that would made him famous. Later I discovered that

many of "his" inventions came from Jewish tradition. Later I found these

stories of my childhood in bookshops under the heading: "Jewish legends".

When my father died, I fell into a bottomless pit and off the

earth I felt left completely alone in the darkness of outer space. Losing

him, I also lost the Jewish world and the contact to his friends. Once, I

saw one of them coming towards me on the street on my way to school.

Before I could run up to him he had crossed the road. At about the same

time, my favorite girl-friend, Veronika, disappeared from my life. Her

mother and another man suddenly took her behind the Iron Curtain into the

Eastern Zone of Germany where they had come from originally.

My mother was so preoccupied with her own mourning that she had

no time for mine. Besides, she had never shared our world. She did not

belong. I felt very guilty, because I felt her to be a stranger and wished

that she had died instead of my father.

After school I had to go to a daily "afternoon-group". For a

short time Tamara, a Jewish girl, also went there. Inexplicably - I could

never put it into words –I felt her to be both extremely familiar and very

alien. Tamara did not stay long because her parents objected to her eating

the pork served to there and the teachers of that group refused to make an

exception.

The Jewish world was buried, deep inside – a ghetto in me. I

knew it was there, but it had no name, no language, let alone

possibilities of expression. Every day I spent hours day-dreaming about my

father.

My mother had fallen in love with a colleague who shifted in

with us a few months later. I did not like Uncle Ernst and even less when

I had to call him "Papa". He was tall and athletic, had cold blue eyes and

had a right-wing position not only in his former handball team. His

favorite subject was the war and his heroic deeds in the SS. They had been

honorable men and had always behaved correctly and decently, he always

told me. Even the Americans had said to him after the war: "Ernst, you‘re

OK" and denazified him quickly. Today I suspect they needed him because of

his qualification.

"We are raped women?" he used to thunder. All lies! Those women

threw themselves at him, he said. He couldn’t get out of their way, they

were so keen on him there, where he was: a guard at the IG Farben factory

making sure that they worked properly. "That school is teaching you a

whole lot of lies" was the regular end of his tirades. There had been no

concentration camps, he claimed. "All lies". There had been work camps but

only for criminals. Under Adolf everything had been better. The autobahns

had been built and the young people were given something to do. "There

were no long-haired loungers on the street smoking hashish, making a row

and listening to jungle music."

My mouth went dry. I thought of Uncle Paul. What stage was I on?

I could not bring these two worlds together. Was I going crazy? There was

no-one I could talk to. Although I had kept a diary since I was eleven, I

had no words to describe this experience of falling apart and dissolving.

I sought a niche in the Protestant Church, and took an interest

in Christianity. Though I was older than the others.the clergyman

suggested I attend his class preparing children for their confirmation. As

he was very attentive and friendly I tried to talk to him. He did his

best, but he found no access to my world. A week before the confirmation

he asked all the children how many family members would be coming to the

celebration so that the appropriate number of seats could be reserved in

the church. All those who answered before me seemed to be coming with

masses of aunts, uncles, cousins, etc. I knew that I could not keep up

with them. Inexorably, it became my turn to answer the question: "And how

many people are you bringing?" All eyes turned to me. "Two," I said

hesitantly. Some laughed, others raised their eyebrows. "How many?" The

question was repeated with astonishment. "Two." "Who?" "My mother and

grandma." "Is that all your family is?" "Yes." I did not want to tell them

that my mother did not speak to her sister. "Oh well, all the better. Then

there is more room for the others." That statement hit me below the belt.

That’s exactly what Hitler wanted. I froze up and fell into an inner

abyss. I obviously lived in a very different world to those around me. On

my father’s side, one uncle had survived, but he had died before my birth.

I had always suffered through the lack of my relatives.

In the mid-seventies I came across the first books for young

people that tried to deal with the Nazi period. Many of the scenes

described were familiar to me. Later, I read Helen Epstein’s "Children of

the Holocaust" and William Niederland’s "The Survivor Syndrome". They

caused inner landslides which I had to dig myself out off; and later these

books helped me to sort out my problems.

I also turned to the Jewish Community. Maybe someone would know

something about my father’s family? Perhaps papers were still? Maybe I

could find out something about my relatives? I had hopes of finding

support and help there, although I had no idea in what way. The response

was a mixture of helplessness and icy rejection. I realized very quickly

that here, too, there was a strict hierarchy: Right at the top were those

who had two Jewish parents. Next came those with a Jewish mother and they

were followed by the converts. Right at the bottom of the ladder were

those with Jewish fathers. I had no chance. However, I wanted to learn to

deal with my family history and hoped to find room to do this in the

Community. That is why I went to a discussion group by a rabbi held

regularly. Five people were there. Two of us were new – a man and I. The

rabbi was friendly to him, asked his name, where he came from and what he

wanted. For some 15 minutes he was allowed to tell his story: two months

ago he had been a Hindu, last month a Muslim and this week he wanted to

become a Jew so that he could experience the universality of the

religions. When it was my turn, the rabbi simply nodded briefly. The

lecture he then held was quite interesting. But when he described the

children of Jewish fathers as "bastards that we have more than enough of,"

I gave up.

I worked as a volunteer in a youth center in Switzerland. The

synagogue and the Jewish Community center were opposite. Many memories

flooded back. Where could I find a place for myself? Several months later

I went to Paris for a few weeks. The Jewish quarter was just around the

corner. Again and again, I experienced the extremes of strong familiarity

and rejection. I wanted to buy some cards for Rosh Ha Schanah in a book

shop. When the obviously Jewish owner heard me speaking French with a

German accent he screamed that he would not sell such cards to Germans and

threw me out of the shop. At home again, I cried for days on end. The only

feeling I had was pain and that I was bleeding to death. Phases like this

occurred again and again. I tried to put all my anger and desperation in

my diary and summed up my experience and came to the defiant conclusion:

"I don’t need a Jewish identity!"

I was in a deep depression. I felt badly treated. Although I

Jews didn’t accept me as one of them, I often enough cowered under

anti-Semitic blows. I became the head of a local community center. The

young people noticed that they could put questions to me about the Nazi

period, which they were not allowed to put at home. Some who knew me

better, knew that my father was Jewish. Ulli was one of them. His group

wanted to organize a disco, but there was no room available at such short

notice. Ulli blamed me. He was furious and shouted: "They obviously forgot

to put your old man into the gaschamber". Again I fell into an abyss!

The Protestant Church’s Adult Education Center held a weekend

for those children of Jewish fathers who felt that they are Jews.

Unfortunately, I found out too late. The Jewish weekly newspaper reported

about this meeting heating upon it scorn and mockery. The headline was:

"Help, the Bastards are Coming."

I was 32 years old when I went to a concert given by an orthodox

rabbi who lived in the USA His songs moved me deeply and I was impressed

by the open-mindedness he showed on the stage. He had grown up in Germany

and represented for me my father’s spiritual world to which I had lost

contact. After the concert I was still inspired by the atmosphere in this

Jewish Community Center that I had not imagined possible when I went up to

him and thanked him. He asked if I am a member of the Jewish Community.

No, I said, my father was Jewish and in this country that puts me into a

very difficult situation. He seemed to understand. He asked for my

telephone number and invited me to take a walk with him on the next day

before leaving the city. He was the first Jew I had met who accepted me as

Jewish without reservations. "Being Jewish is a question of what you feel

in your heart," he told me. For years I clung to this sentence and could

not speak about the darker sides of this encounter.

Namely: in the weeks that followed he rang me up several times

in the middle of the night with the apology that he could not sleep. He

was thinking of me, he told me, and wanted to know how I am. He regretted

that we could not see each other and only talk on the phone. Suddenly the

conversation took an unexpected turn and he began to describe his sexual

fantasies in great detail, his breathe quickening when he spoke. When the

orgasm came, he simply put down the phone without even saying good-bye. I

was paralyzed, shattered and beside myself. During and after my studies

some months before that experience I had worked several years for a

telephone lifeline. There I had had encounters with sex phone-ins whose

only aim was to keep the conversation going until reaching orgasm. In a

professional capacity I had no problem understanding that this

conversation had nothing to do with me personally. However, in this

private encounter with someone who had at last accepted me as being

Jewish, I did not manage to do so. Although I felt guilty and ashamed at

allowing myself to be used in this way, I clung for years to the comfort

of him accepting me as Jewish.

In 1991 I shifted to Berlin. During the first few years I hid

myself, just as I had in the past and my father had always done. Only

three of the many Jews I knew, also knew that my father was Jewish and I

saw to it that those who didn’t know never met those who did. Now ,

however, I have been able to come out of me hiding and to tell my story. I

can see clearly than before that all Jews are challenged to face up to

what the Shoah has meant for their own lives.

In

Berlin there are a few groups on the periphery and outside of the Jewish

community which include numbers of people with Jewish fathers who feel

Jewish but are, like me, not accepted by official Jewish organizations;

and converting has been made impossible in this country except for a

privileged few. I have now found a place in several of these groups for

"If I am not for myself, who will be for me, and being for my own self,

what am I? And if not now, when?" (Hillel)

In

Berlin there are a few groups on the periphery and outside of the Jewish

community which include numbers of people with Jewish fathers who feel

Jewish but are, like me, not accepted by official Jewish organizations;

and converting has been made impossible in this country except for a

privileged few. I have now found a place in several of these groups for

"If I am not for myself, who will be for me, and being for my own self,

what am I? And if not now, when?" (Hillel)